THE GENERAL STRIKE OF 1926,

THE GENERAL STRIKE OF 1926,

THE RHONDDA VALLEY, GLAMORGAN, SOUTH WALES.

For those of you that know very little about this time, I will start by summarising the events before the Dorset Constabulary were dispatched to the area.

The coal industry had declined in production after the enormous output before and during WW1. More pressure was put on the industry in 1924 when Germany was allowed to re-enter the international coal market, to help them get back on their feet. A year later the pound was so strong that it was difficult for industry to export and at the same time the mine owners were trying to maintain their healthy profits.

Over the years miner’s wages had dropped 40 per cent and now the mine owners wanted a further wage drop and longer working hours. As such the industry was at boiling point. The Miners Federation (which started in Wales in 1888) stepped in and along with the Trades Union Congress (TUC) they refused to accept the new terms.

The Government then got involved fearing that the Country would grind to a halt by announcing a Royal Commission would look into the problems of the mining industry. For nine months the Government subsidised the mines and other industries. On 10th March 1926 the Royal Commission published its report which recommended the miners pay be cut by 13 per cent and the Government subsidy immediately withdrawn. The mine owners had got their way and then stated that the miner’s contracts would be adjusted to reflect the report and the miners would also have to work another hour to get the same wages. Naturally the Miners Federation again refused to accept these terms.

Talks were then restarted between the Unions and the Government, which came to nothing, and stopped on 1st May, culminating with the TUC declaring that all industries would stop work at midnight on 3rd May. Frantic discussions were then made over the next two days to stop the first general strike in this Country but neither side would budge. However, the Conservative Government under Stanley Baldwin had been anticipating a strike for 9 months and had already built up a large supply of surplus coal to keep the Country going.

The strike went ahead and about 2 million workers put down their tools. This surprised the Government and brought the Country’s transport to a standstill and the Government, realising the impact, decided to employ a large number of Special Constables to help the Police maintain law and order. On the 7th and 8th of May there were major clashes between strikers and police in most major cities and two days later, the Flying Scotsman was derailed just north of Newcastle upon Tyne at Cramlington as part of the dispute. On 12th May the TUC called off the strike but the miners refused to accept this and over the next few months they stood firm and failed to return to the mines.

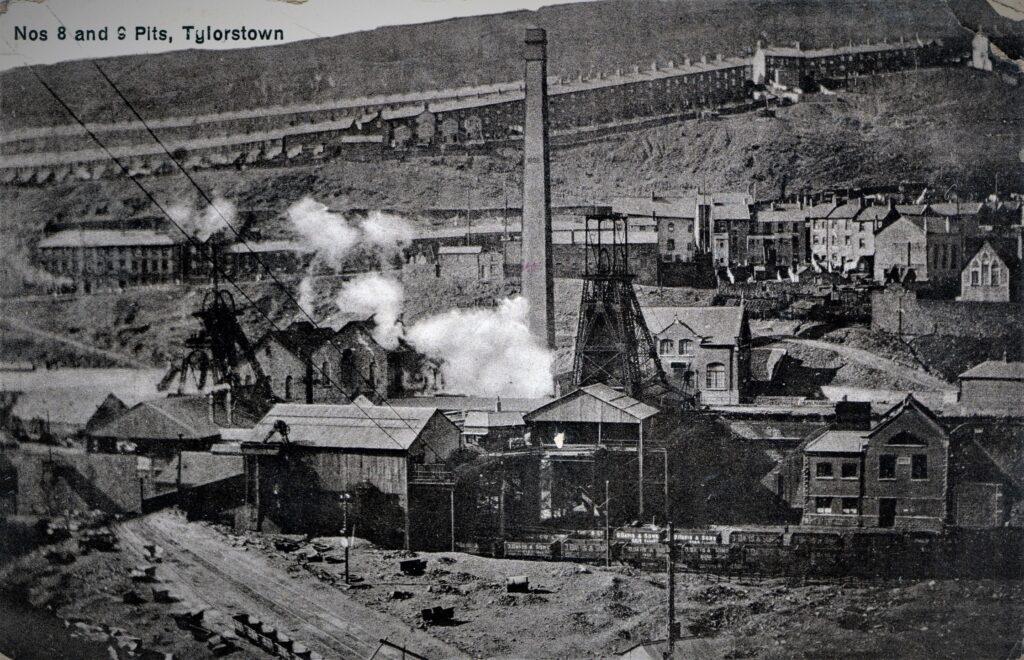

In August there were several disturbances in South Wales in the Ferndale and Tylorstown areas where 47 men were charged with trying to wreck the colliery plant. As tensions rose, the Glamorgan Police were soon looking towards the Government for reinforcements on their streets.

This is Victor SWATRIDGE’S ( PC 27 ) account and photographs of the trip that 50 Dorset Policemen made with additional information and photographs from Herbert Russell PAULLEY (PC 81 ) who was also there with thanks to his gran daughter Joan SMITH.

This photograph shows the Dorset Contingent on arrival in South Wales and two local Glamorgan officers.

.The officers are: FRONT ROW left to right

1: PC Alfred HEAD

2: PC William ALFORD

3: Sgt Edward DAY

4: Sgt William CHASE

5: Glamorgan Inspector, probably Inspector REES

6: Supt Samuel LOVELL

7: Inspector Ernest CLARKE

8: Sgt William COWLING

9: Sgt William BURROUGH

10: PC Sidney OSMAN

11: PC William CUTLER

SECOND ROW:

1: Glamorgan PC, name not known

2: PC Archie LOVELACE

3: PC Arthur OSBORNE

4: PC Bertie HEATH

5: PC Edmund “Dolly” GRAY

6: PC Freddy NORRIS

7: PC George RAWLINGS

8: PC Cyril CHARD

9: PC Victor SWATRIDGE

10: PC Sidney JEANS

11: PC Bob CARTER

12: PC Ernie BEAVIS

13: PC Wilfred SMITH

14: PC Alfred WINTLE

15: PC Francis “ Jack” SPREADBURY

16: PC Reginald BLUES

THIRD ROW:

1: PC Percy GRINTER

2: Pc Reginald CHASE

3: PC Henry WINTER

4: PC Sidney LOADER

5: PC Walter TOLLEY

6: PC Ken PARSONS

7: PC David BLAKEMAN

8: PC William SYMES

9: PC Horace CHASE

10: PC Harry DIXON

11: PC Albert TUCKER

12: PC Arthur MANUEL

BACK ROW:

1: PC Frederick SQUIBB

2: PC James GOODMAN

3: PC Arthur STICKLEY

4: PC George WARD

5: PC John “Jack” CULLEY

6: PC Herbert Russell PAULLEY

7: PC Wilfred Raymond LOCKYER

8: PC Reginald EDWARDS

9: PC George SAMWAYS

10: PC Percy COPP

11: PC Sidney CRUMPLER

12: PC George LILLINGTON

Victor SWATRIDGE wrote this account in his memoirs:

“This was another interesting and distressing period of my career, when the industrial life of the country was at a standstill. The railway network of the country was out of action, only essential needs to prevent utter starvation received attention and the railway men came out in strike to support the coal miners. This had a crippling effect on the country, and it was approaching a state of anarchy. All this was brought about by miners protesting about mine owners wanting the workers to work double shifts and trying to cut the meagre wages.

The police and the military were called in to quell riots and guard vulnerable points. It was industrial chaos, the working conditions and poor pay in mines were intolerable and some pits had been closed for months possibly years. This was the state of things prevailing as a contingent of fifty Dorset policemen were ordered for duty in Glamorgan, South Wales, to assist the local police force as mine workings were being wrecked and public disorder was rife.

On Sunday 17th October 1926, we travelled by train from Dorchester to Bristol, then on to Cardiff where we disembarked and marched through the cobble stone streets of the city to board another train to the mining areas, however these railway carriages were very uncomfortable as there were no springs on the Taff Vale railway. We were heading for the coal mining area of Abercynon where we were being billeted in a couple of hotels.”

POSTCARD 1

“We stayed there for a fortnight awaiting our next orders to proceed to the Rhondda Valley, Tylorstown, the home of Jimmy WILDE, the famous welsh boxing wizard and also to Ferndale adjacent to Maerdy, named in those days as “Little Moscow” where I heard the red flag sung for the first time.

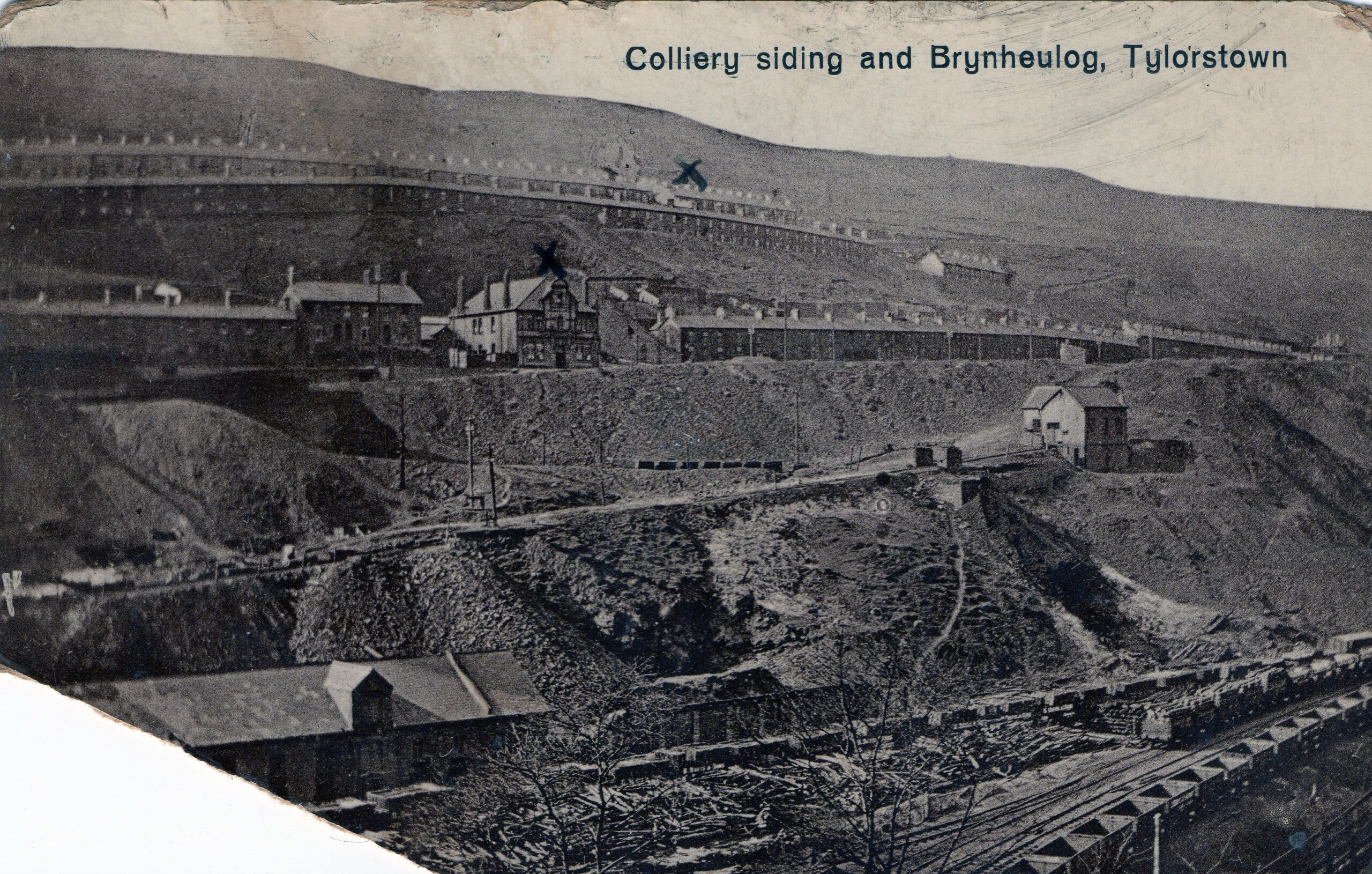

My section was billeted in the Duke of York public house (marked with an X on the below postcard 2 of the area), on the junction of East road and Union Place overlooking a coal workings and a tram way route. All the shops in the area had been closed and boarded up for weeks, possibly months, the scene was most distressing and we were given our instructions to guard working miners, two of them called STIFF, who were father and son. They were described as “black legs” by their pals and they were themselves awaiting trial for crane wrecking.”

(This would appear to be George STIFF and his son John who were being guarded by the six officers. Left to right: I have identified, PC HEAD, GRAY, LOCKYER and MANUEL with maybe PC GRINTER behind the family, in the doorway. Photo with thanks to Joan SMITH.)

“There were five hundred policemen in the area, guarding these two rather despised men, with our contingent were officers from Devon and Brighton Borough Police and we were specially deployed to guard their house in Gwernllwyn Terrace (marked with an X in the next postcard). I vividly remember the terrible slum condition they all lived in, bugs climbed the walls and the rear windows were devoid of glass, rags of all kinds were draped over them to keep out wind and rain and the only thing there of any value was a plentiful supply of coal. One could practically light the coal without fire wood and it gave off a wonderful heat.”

POSTCARD 2

(postcard of the area showing the miners house and the Duke of York public house)

“All the people in the area seemed to be dreadfully poorly clad and men, women and children wore odd stockings in all different colours and the soles of their footwear were down to the base, literally rags, so who could blame them for striking . The police had great sympathy for the majority and our Dorset contingent got on remarkably well with the miners. We listened to their fine welsh singing in the pubs at night, but duty had to be done.

Every day we made numerous baton charges on strikers who collected in groups to stone us, endeavouring to lynch the “black leggers” and devious methods had to be arranged to get the Stiffs home each day in safety.”

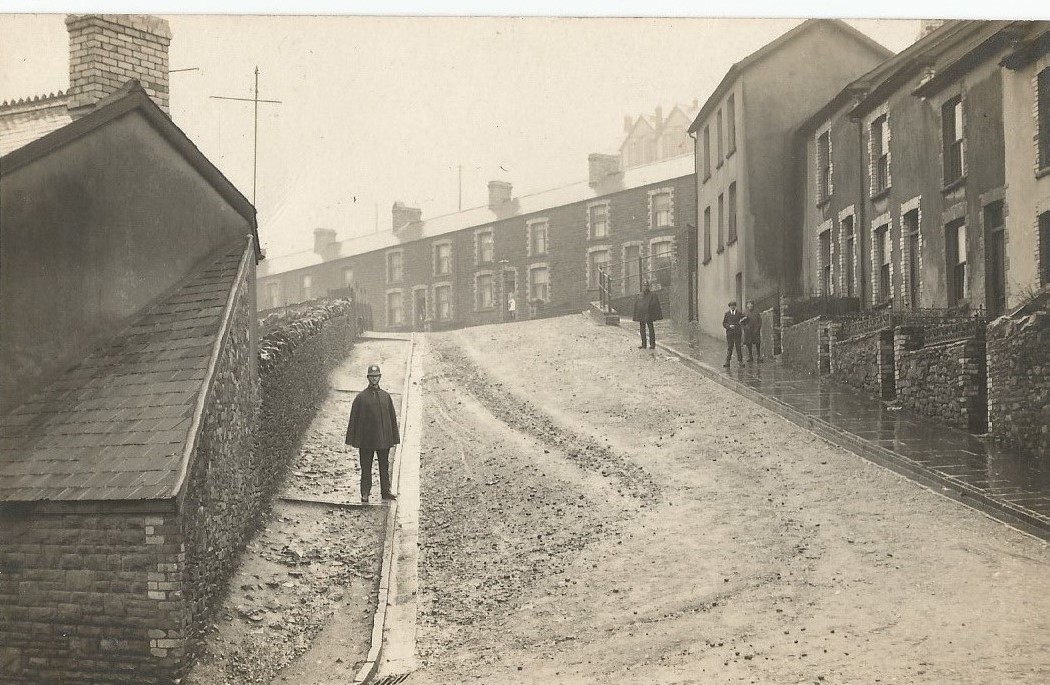

(Junction of Oakland terrace and New street with PC Arthur OSBORNE and PC Jack SPREADBURY, photo with thanks to Joan SMITH.)

“It was the usual practise for the police contingent to prepare for action around lunch time, to escort the two workers from the mine to their home. The Dorset police acted as their bodyguards with the Glamorgan personnel, whilst the other police were used as support. The first instance was to convey the miners from Ferndale Colliery by charabanc, the passengers sat in rows and there was a collapsible canvas hood and the side screens were of semi clear celluloid and were fitted in slots to keep them in position. To support the glass windscreen was wire netting in case any missiles were thrown at it on its travels. Evidently the main body of unemployed miners were all aware of the route and the method of transport.”

POSTCARD 3

(Junction of Oakland terrace and Brynheulog Terrace)

“To illuminate the scene a little more, the roads were sadly lacking in repair and the tramway lines metalled rods were badly worn, in fact if you were a passenger on the very sparse tram service prevailing, it was one of adventure as trams rocked and lurched from side to side, backwards and forwards as they struck badly worn sections, and passengers held on to the rails in the upper deck at their peril to avoid serious injury. The side roads were of flint stone construction and granite chippings were piled in mounds at the roadside and corners, for preconceived purposes. The side streets converged on steep declines on to the main streets and strikers congregated to get sight of the “black leggers” as they returned home to bully and molest them if possible.”

(Junction of Craig Terrace and Oakland Terrace, which was christened Hell Fire Corner showing Sgt Edward DAY and two other PC’S by the tram tracks, photo with thanks to Joan SMITH)

“ I was one of a group of policemen at the road junction known as “hell fire corner”. ( So Vic maybe one of the distant officers above). We saw the charabanc approaching with its passengers and before it reached us it had run the gauntlet of hail showers of granite stones which had been hurled at it with tremendous force so that the vehicle looked like it had been hit by machine gun fire. The whole front of the charabanc was smashed, the windscreen had disintegrated and the front seat occupants were covered in blood. The metal part of the coach body had holes torn through it and the side curtains were a mess. It necessitated us making several baton charges to break up the angry rioters. We were also showered with stones, injuring many of my colleagues, and we became exhausted ourselves chasing the strikers in all directions, up the side streets where they would disappear up alleyways and into any of the houses to make their escape. At one point our superintendent was covered in water after buckets were thrown at him. We made numerous arrests and had to guard our faces from injury by rolling our capes around our left arms and drape them over our forearms, which proved to be fairly effective.”

(Union Place, the morning after a police baton charge in the darkness, with hundreds of stones all over the road used to try and assault the police, photo with thanks to Joan SMITH). I think this black and white photograph really captures the conditions at the time and the feeling of poverty.

“On another occasion we changed routes, walking the “black leggers” through various mine shafts and we came up by different cages to the surface, yet the baton charges still persisted for several days and the whole scene was very exciting and dangerous. We eventually made three hundred and ninety arrests for various offences and cases were dealt with in court for several weeks. In adition we were on guard day and night at the “black leggers” home, where half a dozen men did duty on four hour shifts inside and out.

When the workmen returned home it had its amusing side to the family life of the miners. They always stripped off their clothes in the kitchen, hurling their grubby clothes under the couch or in the corner of the room in a heap and bathed naked before the women and children and friends and neighbours, afterwards putting on a flannel vest and a change of clothing and in the morning re robbing in their grubby working clothes, living was a mere existence for them.

The sheep roamed the streets and alleyways rummaging in the dustbins for scraps of food and potato peelings etc. Children did likewise whilst the men went up on to the mountainous slag heaps digging away at the rubble to find any lumps of coal. There was a state of huge depression, shops had been closed for weeks but somehow people existed on a near starvation diet. We even had bad food conditions, being served at dinners with fat mutton soup as a main course, where the residue stuck to one’s lips. “

(A photograph of the Dorset contingent with the Glamorgan and Brighton Constabulary, which Joan SMITH’s grandmother had on a wall in her house.)

“Whilst we were there another thing that surprised me was the terrific capacity for drink of our Glamorgan colleagues. Beer was contained in quart flagons and they were devoured by some like cups of tea, in one long gulp and similar to pouring it down the sink, drunkenness was pretty prevalent. The superintendent in charge of them was named Rees and one of his brothers was an inspector, both had been demoted for drinking on duty but that did not deter them from rising to their former ranks again.

Anyway, it was quite a worthwhile experience to realise the living and working conditions of other sections of the community. It was a real pleasure to return home in early December to our native county and its cleanliness and quietude.”

In the Western Gazette on 10th December a small article was written entitled “ Return of Dorset Police. The article summarised all of incidents that occurred during the troubles. It also made mention, that during the worst times, the local community were worried about their children.

“ Much anxiety was felt by parents for the safety on their children, many of whom were due to come home from school at the time the rioting was going on, and had to pass through the streets that were the scene of the rioting, to reach their homes. The teachers fearing injury to the little ones, escorted them to their homes. Although the experiences of the Dorset policemen, since their arrival at Ferndale have been sufficient to ruffle the sweetest tempers, they good-naturedly threw coppers to the kiddies as they passed”

In January 1927, some of our contingent including Superintendent LOVELL returned to Wales to attend Court, as a result of all the terrible rioting that took place mainly on the 1st, 2nd and 3rd of November, when charges of criminal damage, intimidation and riotous assembly were heard. Over one hundred defendants, many of them women attended the police court at Porth, near Tonypandy. Supt J L REES from Pontypridd gave evidence that on Nov 3rd, when at Ferndale, assisted by Supt LOVELL, he and other officers were escorting George and John STIFF back to their home in Gwernllwyn Terrace in a tram car. An angry mob confronted them and smashed all the windows and for two hours there was guerrilla warfare, where about seven to eight hundred were chased through the valley by about thirty policemen for about 2 miles until the riot was quelled and the mob were moved on. He along with Sgt A R HILL and PC JENKINS reported that because of the stone throwing, the Dorset officers who were injured on that day were, PC GRINTER,( Wimborne ) who had a finger injury, PC LOADER (Lyme Regis) was struck on the right hand and PC LILLINGTON ( Okeford Fitzpaine ) was struck on the mouth. PC GRINTER was off work for a month because of his injury. All the defendants were committed to trial at the Assizes.

At the Glamorgan Assizes in February 1927, twenty six men and nine women charged in connection with the riots of November 3rd 1926 were on trial for five days. All were found guilty except four men and four women. All were given terms of imprisonment and one man called Alfred PARSONS, who was 22 years old was given six months hard labour for assault on Supt LOVELL when he violently struck his helmet, and four more were given a sentence of 3 months hard labour. The local MP Lt Col D WATTS-MORGAN wrote to the Home Secretary asking for leniency for the imprisoned women, but the Home Secretary after looking into their cases decided the punishments would stand as their children were being looked after by either friends or neighbours.

As a result of our good work, the services of our contingent, were recognised in official circles on Wednesday 22nd June 1927 when Supt Samuel LOVELL attended Buckingham Palace and was awarded the British Empire Medal on behalf of the Dorset Constabulary.

Below is another photograph Joan SMITH has shared, which shows a close up of presumably Supt REES, (Glamorgan police) Supt LOVELL (sat down) and Insp Clarke, both of Dorset, prior to LOVELL receiving his BEM.

Footnote: The STIFFS lived at 35 Gwenllwyn Terrace according to the 1911 Census and were more than likely still living there in 1926, however the terraced house has since been demolished and now a bungalow stands in its place.