Victor Walter SWATRIDGE, my grandfather, was in the right place at the right time being a police Sgt at Dorchester in WW2 . He witnessed many local incidents and especially the build up to the finale of WW2.

When I think back to all the information I have read about those times, (way before I was born) , I think about those men that were sent abroad to fight on the front, some losing their lives. Then I think about their fathers, those that served in WW1 and now their sons that were the right age to follow in the father’s footsteps and again, had to fight for King and Country.

My family were VERY lucky, as time wise, not many in my family were the right age to be involved and sent to the front. My grandfather was born in 1901, so Vic was too young for WW1, although some of my Uncles did survive being sent to the front. Then in 1939 for WW2 my father and my Uncles were also too young.

So my family escaped the horror that other families did not, and that is probably why I was born and why I can report on it.

After WW1 in late 1919, many Dorset Constabulary officers had to be recruited as 5 had been killed, others decided to not continue for whatever reasons, but possibly it was related to the horror of being on the front. Then, there were all the senior policemen back home in Dorset, whatever rank, who wanted and deserved to retire after doing more than their alloted time, and now being passed their pensionable age.

There always seemed to be plenty of men waiting to join the Force, including my grandfather, but it was a priority of the Force to take on those men that had served their country during WW1. Roughly half of the Force needed to be recruited as Dorset were in the poor position of needing to replenish quickly to replace those that had been waiting years to retire.

One of the family’s that served in both wars were the OLIVER’S. Charles Oliver served in WW1 and his son Roland in WW2. There are or rather were many others !

Vic wrote in his memoirs: On the 21st February 1939, I commenced my duties as a Divisional Sgt at Dorchester, being one of only two constables in over ten years to attain promotion from the Sherborne Division. After 16 years as PC 27, I was now a Sergeant and my number changed to 1, taking over Sgt Hubert SCREEN’s number and position. My wife had already sowed on my Sgt Stripes on my tunic the night before and I was looking forward to going back to Dorchester and Head Quarters which had been part of my childhood.

Early that morning about seven o’clock the furniture van arrived, which as part of my responsibilities was mine to order and the officer (me) paid so much per mile to the company, and the longer the better, as the police officer would normally come out with a few shillings to his advantage. Everything was packed methodically in boxes before the day to ensure no breakages, floor lino and carpet first if you had any, and bedsteads and mattresses last. This enabled the incoming tenants to hurriedly lay the floor covering and then the main furniture such as wardrobes, cupboards etc could be put in place with as little convenience as possible. Then curtains were hurriedly hung in the windows to make things habitable and the final touches would have to be done later to our home at 1 Mountain Ash Road.

Once that was done I had just enough time to have a quick meal and then report for duty at five o’clock, evening time for about five hours. These were still the days of one or two days off, more than that were not permissible. Work first, comfort afterwards was the rule and the wives had to make the most of their time to make the home their own. The main consideration for me was that I was promoted, and in the eyes now of the bosses. The financial renumeration I was now entitled too made me feel more important and could give my wife and son a better way of life and gave us a few more meagre luxuries. We were able to pay our way a little easier and I was able to get away from the more menial tasks of a constable, yet never the less long hours were worked and overtime was common place without the slightest thought of payment for extra duty or time off, it was all part of the Service.

We had hardly had time to settle in our house, which overlooked the Dorset Depot Barracks, when we told to pack our things again to move to 10, Damers Road which was being vacated by Mrs SCREEN. The reason why I was promoted was because unfortunately Sgt Hubert SCREEN had died suddenly at Dorchester and now his wife (and family) had been able to get their life back on track, the house was now vacant. The address was recognised as a Sgt’s house as it was semi- detached and next to another Sgt’s house, basically it was thought to be a good policy to keep the same ranks together to avoid familiarity with other ranks. Next door was Sgt Freddy MALKIN who was not there long before being moved on to the Wareham Division.

At the time Hitler ( moving on from desirable Dorchester) was dominating European affairs and as supreme leader of the German nation marching his armies into countries surrounding Germany and Austria and Hungary were forced to accept his dominance. Neville Chamberlain was Prime Minister of Great Britain and the Government realised that if a stand was not made, other countries closely allied to the British Isles would suffer the same fate. Yet virtually we as a nation were defenceless although it was always our proud boast that the British were the defenders of our less fortunate neighbours.

Hitler had just marched into Czechoslovakia and as a result on Monday 13th March a special meeting was quickly arranged at the Shirehall for the Dorset Standing Joint Committee. The Chief Constable discussed confidential documents he had received from the Home Secretary that approved the formation of a Police War Department. It was decided that there would be a Chief Inspector, supported by a Sgt and a PC at HQ who would be responsible for the administration and training of all Police Auxillary services, the Special Constabulary, First Police Reserve, the Police War Reserve which was not yet formed and also the Observer Corps and A.R.P Wardens.

There would also be Inspectors at Weymouth and Poole and Sgt’s at Dorchester, Wimborne, Sherborne and Bridport at a total cost of £2,700 per annum. This figure did not account for pensions, housing, uniform or travelling and I was hoping to be part of the department with all my previous involvement of aliens at Sherborne however I had only been promoted for a few months so knew it was unlikely. TO BE CONTINUED.

The original articles appeared in the ‘Dorset the County Magazine’.

Articles copied and added to the Facebook Group ‘Bygone Dorset’, by Carole Dorran.

October 2019.

WAR IN DORSET: AN ACCOUNT BY VICTOR W. SWATRIDGE, POLICE CONSTABLE

**Part 1. [Source: my copy of a 1971 issue of ‘Dorset the County Magazine’].

Dorset is a delightful part of the kingdom of Wessex and I belong to a traditionally police family with over 150 years’ service in the Dorset Constabulary and on looking back many incidents come flowing back into my memory.

I have lived through two world wars in which the German nation has been our principle antagonist. My father from 1910 to 1920 was Superintendent in charge of the Sherborne and Shaftesbury Division and I remember him recalling on several occasions, a conversation he had with a Miss Von Bissen, a Music Teacher in a renowned Ladies’ High School. She was the sister of General Von Bissen a Corps Commander of the German High Command of the Kaiser’s Army, and spoke of the desperate need of the world-wide expansion of the German people to give them living space as “God’s Chosen People”.

She arrogantly stated that the time was ripe for the German race to dominate the world and shortly afterwards in 1914 the first world war began. Then it was somewhat commonplace for 30,000 British troops to be killed in a day’s battle when men were mown down by gun fire as ceaseless waves of human fodder were hurled into the inferno. Terrible slaughter was experienced on both sides until Germany surrendered to defeat in 1918. It was stated to be “a war to end all wars” and that the German nation must never rise in strength again.

In the 1930s Hitler ascended to power, succeeding Field Marshal Von Hindenburg as head of state for Germany. He was rallying the people into political frenzy and excitement and in his greed for power was systematically marching his armies and annexing the smaller countries surrounding the German borders, making easy conquests and without resistance. The Hitler Youth Movement was spreading its influence into other European countries in preparation for world dominance once more.

I joined the Dorset Constabulary in 1923 and from 1934/39 I was the Aliens Officer at the Divisional Headquarters at Sherborne being responsible for the registration of many aliens of German nationality, who arrived on “work permits” to take up employment as domestic servants. They were young women who strangely enough all had an excellent knowledge of the English languages and intellectually much above the servant class. They worked in the homes of high ranking officers of the Army and Navy, many of whom being retired in this part of the country. In addition, I had to register a man of magnificent physique, a young blonde Prussian named Heinz Brack. He was engaged as a language tutor in one of our famous public schools, the students being sons of the leading aristocracy of Britain.

Brack was a most charming man and regarded as a delightful person by his associates at the school. He quite often paid visits, under any pretext, to the Divisional Office, which aroused my suspicions and when I refused the information he required, became arrogant and demanding. Discreetly and unobtrusively I introduced the name of Heinz Brack into the conversation when dealing with new female arrivals and those returning to their homeland. On mentioning the name, there was a distinct change of attitude which carried with it a frightening expression on the faces of the aliens. I intensified my enquiries and found that Brack was away from his lodgings every weekend, travelling extensively in the south-western counties. I was confident that he was busily engaged in subversion and had a great influence and control of German nationals in this area, possibly part of an espionage network.

Neville Chamberlain at this time after a meeting with Hitler, having both signed a treaty of non-aggression, returned to this country delighted with his successful mission, but Hitler immediately broke his pledge by marching into Poland. Britain declared war on Germany and I ensured that Heinz Brack was quickly arrested and interned for the duration of the war.

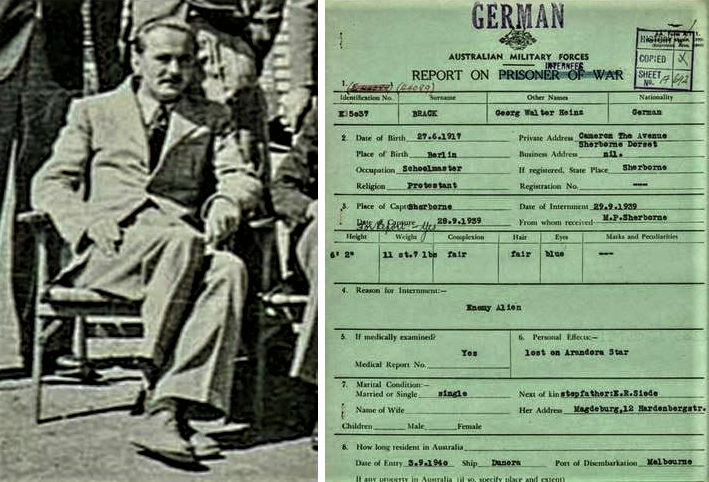

Photo: Heinz Brack.

Part 2:

If you read Part 1 of the account from the Dorset constable during WW2, you might find this story interesting.

On the 3 September 1940, a year to the day after Britain had declared war on Germany, Captain A.R. Heighway, the

officer-in-charge of the Australian Prisoner of War Information Bureau, signed a detention order for one Georg Walter Heinz Brack, ‘being an enemy alien on board His Majesty’s Transport “Dunera,” who has been sent from the

United Kingdom to Australia for internment.’

Born in Berlin in 1915, Brack had come to Sherborne School as a young graduate in 1936 to help out temporarily in the Modern Languages Department where he taught intermittently until 1939. Brack had been recommended to

Headmaster A.R. Wallace by one of the School Governors, Professor John Murray, then Principal of University College, Exeter.

Brack was apparently a delightful young man and a good teacher but, as relations deteriorated

between Britain and Germany, the Headmaster became uncomfortable about Brack’s reasons for being here and even had him tailed by Scotland Yard whilst away from Sherborne on holiday.

Evidently, the Headmaster was not the only person in Sherborne to have his doubts about Brack. Victor Swatridge, the Aliens Officer at Police Divisional Headquarters in Sherborne, recalled in later years, how ‘I had to register a man

of magnificent physique, a young blonde Prussian named Heinz Brack. Brack was a most charming man and regarded as a delightful person by his associates at the school. He quite often paid visits, under any pretext, to the

divisional office, which aroused my suspicions, and when I refused the information he required, became arrogant and

demanding… I intensified my enquiries and found that Brack was away from his lodgings every weekend, travelling extensively in the south-western counties. I was confident that he was busily engaged in subversion and had a great

influence and control of German nationals in this area, possibly part of an espionage network.’

On the evening of 27 September 1939, Brack turned up at School House while the Headmaster and his family were having dinner. On being asked why he hadn’t returned to Germany to fight for his country, Brack replied that he found it impossible to fight against his former friends and so had remained in Britain. The Headmaster gave him a

bed for the night and then handed him over to the Military Police the next morning.

It later transpired that Brack had been a Nazi agent responsible for collecting information about Germans living in Dorset. After his arrest, Brack was sent to an internment camp and on 1 July 1940 was put, with over 1,200 other German

and Italian internees, on the SS Arandora Star at Liverpool, bound for internment camps in Canada.

However, the next day the ship was sighted by U-47 commanded by Günther Prien (one of Germany’s top U-boat aces and

responsible in October 1939 for the audacious sinking of HMS Royal Oak at the Scapa Flow Naval Base) and torpedoed with the loss of over 800 lives. Brack survived, but lost all his possessions.

However, this was not the

end of his ordeal for just nine days later he was put with 2,542 internees on HMT Dunera at Liverpool, this time destined for internment camps in Australia. The voyage of HMT Dunera to Australia was later described by Winston Churchill as “a deplorable and regrettable mistake.” The ship was hugely overcrowded and the conditions were

appalling with men kept below deck for all but 30 minutes a day and fresh water supplied only two or three times a week. When HMT Dunera arrived 57 days later in Melbourne, the Australian medical army officer was shocked by

the conditions he found on the ship and his subsequent report led to the court martial of the officer-in-charge.

Having arrived in Australia, Brack was placed in Tatura Internment Camp (no.1) in Victoria. Camp no.1 was built in 1940 and was Australia’s first purpose-built internment camp. It housed single males, mostly German and Italian internees, and over the next five years the internees developed tennis courts, workshops, a newspaper, and flower

and vegetable gardens.

Photographs of the Tatura Internment Camp held in the Australian War Memorial Archive show a happy and healthy-looking Brack with fellow internees.

Following the surrender of Germany in May 1945, Brack was transferred back to Britain on the QSMV Dominion Monarch, arriving in Liverpool on 2 August 1945 in considerably more style than he had left five years earlier. But Brack’s story does not end there. He returned that year to his home in Magdeburg and was immediately arrested by the Russians on undisclosed charges and kept in confinement for ten years.

On his release he moved to Bonn where he took up teaching again, but died there in 1966, aged just fifty-one.

Photo: Heinz Brack (front row, left-hand side) with a group of German internees at Tatura Internment Camp, 13 February 1943.

[Source: The Old Shirburnian online, with the permission of their archivist].

Part 3

Several incidents in the earlier stages of the war spring to mind – an ammunition ship received a direct hit by an enemy bomb in Portland Harbour; there was a terrific explosion with heavy loss of life amongst the crew. This was the first real indication to me of the seriousness of enemy bombing raids on this county. Another was when a German bomber was shot down by anti-aircraft fire over Portland and completely disappeared in a huge crater near the northern gate of the Verne Barracks, now an outbound prison. Portland is a massive solid stone peninsula jutting out from the mainland and it is extremely difficult to realise that an aircraft could plunge into this rocklike surface without trace of craft and crew.

Warmwell Aerodrome was then of very modest proportions and only accommodated the training of pilots in the preliminary stages. There was a solitary large type bi-plane based in a hangar there; its speed was of snail pace by modern standards. It would climb slowly into the sky and it seemed ages before it reached its height, a sitting target for any fighter plane but went on endlessly without interference; in fact, it came up at regular intervals. It appears laughable on reflection when realising the terrific speeds of aircraft today and rockets travelling to the moon. Warmwell was later developed into a Fighter Station, squadrons of Hurricanes and afterwards Spitfires being used to combat enemy bombers raiding this country. Often they would be seen rising off the ‘drome making for the English Channel, even before air-raid warnings had been sounded and on many occasions I witnessed air battles raging in the skies and planes spiraling down in flames – exciting days.

The enemy bomber forces focused their bearings on Portland and the Wireless Station at Winterborne Abbas when raiding many of our principle cities, docks and marshalling yards at Bristol, Cardiff, Birmingham and the north. There was never any real attempt to destroy the Wireless Station or Dorchester, although it had its exciting moments. I remember on one occasion, I was preparing for night duty patrol at about 9 pm and German bombers were returning to their bases in France having carried out a raid inland. Fire bombs were being extensively used by the enemy in an endeavor to wipe out industrial centres and create huge areas of fires, when suddenly incendiary bombs were rained down on the town and district. The whole area was transformed into “fairyland” and the surrounding woodlands were alight with phosphorous bombs igniting. It was the usual practice for high explosives, accompanied by huge oil and incendiary bombs to make a mass conflagration. In this particular instance, oil bombs dropped immediately adjacent to both cinemas in the town, which were packed with audiences, but neither exploded in flames and fortunately, no loss of life was experienced and the town escaped with minor damage. Yet thousands of bombs were dropped on its perimeter; all bombs dropped in the county were charted on huge maps at Police Headquarters, which gave a vivid visual picture of events.

“Butterfly” bombs, an anti-personnel device, were another method adopted by the enemy, mainly for the purpose of lowering the morale of the civilian population. Initially very little was known of their destructive force, beyond the fact that the bombs were contained in canisters of 50 and on release the canisters would open out and the contents would flutter down spreading over a wide area. The bombs were about the size of a pound jam tin, painted yellow and with winged attachments, highly sensitive to touch if picked up or disturbed and liable to explode with devastating effect to the person concerned. It was usual for “H.E” and oil bombs to accompany the canisters. A restricted number of police officers, mostly Sergeants, were trained as Bomb Recognizance Officers and this included special tuition for charting the “Butterfly” bombs to enable the Army Bomb Disposal Squad to deal with them with safety.

A batch of these anti-personnel bombs was dropped on the tiny village of East Lulworth immediately adjacent to the Weld Estate; the police were informed and a search party dispatched. I was included to assist in compiling the chart under the direction of Bomb Recognizance Officer, but he was hurriedly called away on other duties and I was left in control without any form of training. I might add that I did not relish the task but the job had to be done even in the face of serious injury. It was approached with extreme caution and a large oil bomb, unexploded, was found lodged in the thatched roof of the public house. We accounted for 49 of the 50 Butterfly bombs – highly satisfied with the effort but this did not meet with the approval of the Divisional Superintendent, who ordered a further search. To my knowledge the lone bomb was never discovered and could easily have exploded in the wooded area. These devices were continually thrown at us by the enemy and we had to learn the hard way by personal trial and error.

The incident illustrated just how ill-equipped we were, although, the nation was gradually and progressively welding itself into an effective fighting force to combat the enemy, a tremendously tedious task.

Total number of casualties in the County

Killed – 280

Seriously injured – 237

Slightly injured – 358

‘This is a reproduction of the map kept by the Dorset Constabulary showing bombs and crashed aircraft which fell on the County during the 1935 – 1945 War. Many Anti-personnel bombs were dropped in various parts of the County and are not recorded on this map.’

Part 4

Churchill appointed Lord Beaverbrook as the Minister of Aircraft Production, as Britain desperately needed to build a huge bomber and fighter force. In the meantime the enemy became more daring and adventurous. In addition to the mass bomber raids at night, they carried out daylight raids by fighter bombers on coastal towns and other targets, dropping smaller numbers of bombs in “hit and run” raids. They gained considerable success initially at places like Poole, Swanage, Weymouth, Warmwell Aerodrome, etc. Planes would dive in at high speed, low altitude and under the radar screen. These sporadic raids caused loss of civilian lives and considerable damage, keeping everyone constantly on the alert – night and day.

Enemy agents were infiltrating the country and close watch for parachutists was kept and a constant vigil maintained.

At 2.44 am on a bitterly cold winter’s night in January, I was on duty in the Divisional Office when a telephone message was received from the constable on the Broadmayne Beat that a Spitfire Fighter had been stolen from Warmwell Aerodrome at 02.20 hours and flown in a westerly direction. The officer sending the message was known to me as a practical leg puller and capable of playing a joke on anyone. A blizzard had been blowing all night and there was a heavy coating of snow. The position appeared farcical at first and positively ridiculous, even for a highly skilled pilot under such terrible conditions. Anyway the incident was perfectly correct. On contacting the town patrol constable, he assured me that he had heard a plane overhead at about 2.30 am and this was confirmed by the Observer Corps stationed at the post on Poundbury. It was recognised as a British aircraft and after circling the town was last heard and charted in the area of Chesilbourne, about 6 to 7 miles north-east of Dorchester. The snow storm had abated and it was moonlight; I decided to take action and with another officer went by car through the narrow country lanes and arrived on Chesilbourne Downs, where at a vantage point we were able to survey the valley but without result. We thought it would be a fruitless journey but decided to press on. At about 5 am on approaching Chesilbourne Water, to our amazement we saw a lighted hurricane lamp in the drive to a cottage. Naked lights were regarded as somewhat treasonable and very much frowned upon, as black out regulations were strictly enforcible. Even the headlamps of cars were only allowed narrow slotted beams.

I immediately investigated the reason for this breach and a woman, on answering my call at the cottage, stated that she had heard a plane overhead about 2 hours previously which appeared to have landed nearby. She went on to say, that she had been expecting her husband home on leave from France and it was the sort of stupid thing he would do, come by any means possible. She had placed the lighted lamp as a guide to him. Amazing as it seemed, we trudged on and clambered on to a high bank overlooking an un-ploughed cornfield where to our utter surprise we came upon tyre marks. On following them we found the missing fighter plane with its nose embedded in the hedge and bank at the other end of the field, on Eastfield Farm a quarter of a mile N.E. of Chesilbourne Church.

Climbing on to the wing we found the cockpit light burning but the “bird” had flown. There was no trace of blood inside and we found footmarks in the snow made by the culprit, when walking away from the scene, but they quickly became extinct owing to the drifting snow. To cut a long story short I returned to the Divisional Station, after leaving a constable to guard the plane and a search party was sent out in daylight and a Canadian airman of the ground staff was arrested, having celebrated too liberally the previous night and in a rash moment embarked on this venturesome journey. There was only slight damage to the aircraft, the man was concussed and later dealt with by the authorities, so the escapade resolved itself.

Part 5

Information was received that the enemy was stepping up concentration in the bombing of industrial and aircraft works; a daylight raid on a foggy afternoon was no doubt intended for Westland Aircraft Works at Yeovil, but unfortunately, the bomber force was off-target and the market town of Sherborne nearby suffered considerable loss of life and destruction.

The bomber force was returning to its base in France, the sky was clearing as it passed over Dorchester and the mass of aircraft was plainly visible. I was watching it in my garden with another police colleague, when a lone Spitfire Fighter had the audacity and courage to attack it. The rattle of cannon fire was plainly heard as the plane swooped underneath the bombers. My house adjoined some allotments in Damers Road, Dorchester. As we watched this thrilling dog fight, there was the screeching of a bomb immediately above, hurtling to earth. We threw ourselves on the ground to avoid the blast of the explosion, whilst our families were sheltering in a home-made shelter. There was a dull thud and on clambering to our feet saw there was a huge crater in the allotments about 50 yards away. We commented on the fact that there had been someone digging near this spot and ran towards it. On doing so a man, a well known Southern Railway Guard, rose to his feet on the lip of the crater and his allotment had practically disappeared. A number of youths were amongst the sightseers and in their excitement trampled on the remaining portion, much to the annoyance of the gardener, who shouted, “Hi! Get off my allotment, I’ve only just dug my potatoes”. The man was shocked but uninjured and had a remarkable escape. The amusing thing was that he was more concerned about his potato crop than the havoc wrought by the bomb.

I have often wondered why the odd bomb? Perhaps the bomber pilot thought it better to dispose of it, rather than carry it back to base or was it just an act of reprisal because the lone Spitfire pilot had the audacity to daringly attack the mighty German Bomber Force?

One winter or early spring afternoon it was reported that a French two-seater civilian plane had landed at Stinsford and the occupants had surrendered themselves as refugees, fleeing from the oppressors and wishing to assist the allied cause. They were brought to the Division Headquarters for screening by the War Intelligence Branch. I was delegated the responsibility of guarding the two men. One of them told me that he had been waiting for months for an opportune time to escape. The plane had been hidden in a wood near the French coast bordering the English Channel and he related in detail how they had to cut down a number of large trees to enable sufficient runway for the plane to become airborne. The police were constantly on the alert regarding enemy agents infiltrating this country and it was extremely important for prolonged screening of any such escapees.

The men were unable to convince the Special Branch Officers that their story was authentic. They were taken to the Tower of London for a prolonged interrogation, where one was found to be an enemy agent. I had a momento of the occasion in the form of a French cigar, which I retained for several years.

Part 6

It is not very widely known that Brownsea Island was used for screening thousands of refugees immediately after the evacuation at Dunkirk and was a clearing station, ideally suited for the purpose.

The North African Campaign had been successfully concluded, and the 1st American Army Corps were transported to this county and based in Dorchester. All halls in the district were commandeered to accommodate the troops and several turned into cookhouses and canteens.

Prior to the arrival, an advanced party of soldiers direct from the USA was engaged at Kingston Maurward assembling a huge petrol depot. Numerous excavators and lorries were employed and the personnel were mostly men released from an American penitentiary to assist in the war effort. They worked very hard and in their free time became extremely fond of the English drinking habits, especially enjoying the taste of whisky and spirits, which aroused their excitement. The Tommies, their counterparts, were unable to indulge so liberally, as money was not so freely available.

The American contingent visited town as frequently as possible and when the public houses closed at night, temperaments sometimes clashed. On one occasion I was on night-duty patrol in the town centre when a party of American soldiers headed by a ginger-headed fellow named Red Campbell, who was “top man” and exercised considerable influence amongst his pals, were setting the town alight and arguing amongst themselves. I had to step in to avoid any unpleasantness in an effort to get them to disperse and return to Kingston Maurward. Red immediately challenged my authority and was not entirely au-fait with police jurisdiction in this country. He clawed hold of my tunic, tearing buttons out and evidently thought he controlled everything and everybody he surveyed. I quickly assured him that this was not the case and that he must accept our laws when away from his unit. The position was a little precarious for me and the situation could quickly have got out of hand, as a crowd of British Tommies was standing by eagerly wanting to assist us and join in the affray. With the assistance of some additional policemen we managed to shepherd the Americans into a side street, at the same time advising our own troops to return to barracks. Eventually, the American Patrols arrived by lorries and the personnel returned to Kingston Maurward, where I later reported the incident to the Commanding Officer.

This was my first experience of American troops but it led to an excellent relationship with numerous US contingents throughout the war, although other incidents did occur and racial problems were very much in evidence even in those days.

As the war steadily wore on, vast preparations were being made by British and American Armed Forces for the impending invasion of Europe and the morale of troops was greatly improved, especially after visits by Generals Eisenhower and Montgomery. I remember them making rallying soap box speeches to thousands of soldiers packed into the parade ground at the Depot Barracks, Dorchester, at a Sunday lunchtime. Everything was highly secretive. I was one of a party of policemen in attendance and the occasion caused great enthusiasm and the speeches gave us all a tremendous uplift.

It was apparant “D” Day was fast approaching; massive American troop movement was continually taking place, roads were being torn into most of the large woodlands in the district to act as reception centres and as a means of camouflaging of vehicles and men assembling in huge numbers. In the town itself, troops and armoured vehicles took shelter in the tree lined streets. There was constant movement, all being congregated to eventually embark at Portland Hard on Chesil Beach.

Amongst all this noise and movement of men and vehicles, a simple unique incident occurred, which has always stuck deeply in my memory; a tiny bird decided to join in, a nightingale came to town and charmed everyone by its magnificent song. It roosted in a low tree in Gloucester Road, near my home, immediately above the armoured vehicles and refused to let anything disturb it. Nightingales are extremely timid and shy birds, rarely, if ever, sheltering in towns. I have never known such an instance before or since. This little songster stayed static for about a month and every night it could be heard loudly singing all over the town. It brought complete peace and serenity in the midst of a raging war. My wife and I, like many others, made cups of tea and shared them with the American soldiers and we all commented on this little bird in the quietude of the early summer nights. The bird vacated its perch immediately after the troops had left. I often wondered how many American soldiers still remember that nightingale?

Part 7

On the night of the 5th June 1944, I was patrolling in Victoria Park, Dorchester, with the intention of making a conference point with a beat constable at 12.30 am. Britain was still suffering from its black out and not a glimmer of light dared emit from any house or premises. It was a beautiful clear starlit night, when suddenly I became aware of the heavy drone of aircraft coming from inland. As it drew nearer, the sky lit up: thousands of coloured lights had burst forth and the whole atmosphere exploded into activity. It was an amazing transformation as hundreds of bombers towing gliders with their masses of human and vehicle cargo flew overhead and across the English Channel. This huge armada was a continuous procession for more than two hours. It was clearly evident that the invasion of Europe had commenced and I remember how excited I was. Yet still the civilian population were still quietly sleeping in their beds; everyone had become immune to the noise of aircraft travelling overhead, yet I venture to suggest if it had been enemy planes, the whole place would have been alive with activity, as sirens would have wailed and woken them from their slumber.

Invasion Day had been very secretively guarded; everyone had been warned that it would be treasonable to give the slightest indication to the enemy that it was about to take place, and the civil population kept that bargain. The police had been warned to expect heavy counter bombing and we were expecting frightening reprisals. We waited but no enemy air action occurred to our utter amazement. It seemed an act of God and it appeared that our wildest prayers had been answered; the hammering of enemy bases by the allied air forces had taken its toll.

I returned hurriedly to headquarters, still anxiously awaiting events, and after a short break hundreds of our planes came limping back, many of them with engines spluttering and barely above roof height. We quickly began to realise that the invading forces must have received severe destruction of life and aircraft, and we were all sad at the thought that thousands of brave men, British and American, had sacrificed their lives for us and the love of their countries. They were now locked in mortal combat for survival. Again I hate to think what would have occurred if we had not eventually succeeded. I fear millions of Britons would have been exterminated by Hitler. On looking back over that night, I realise how wonderful it is to be British and able to enjoy freedom of speech without the fear of death and persecution. I shall never forget it.

Hitler eventually admitted defeat by committing suicide, and his edifice dramatically collapsed. Most German cities had been literally razed to the ground. The signing of armistice was accepted by Field Marshal Montgomery with great relief after over six years of total war. Victory celebrations took place all over the country. Every street in every town and village in Dorset had its party. Tables, chairs and buntings were arrayed everywhere and there was a partial relaxation from food rationing. All was thrown into the common pool and shared to the merriment of all concerned. There was feasting, dancing and singing with liberal amount of intoxication, yet everyone joyously entered into the spirit of revelry and thankfulness. We all then vowed that there must never be a third world war and that future generations must not witness the terrible slaughter of humanity and privations that we had experienced.

Dorset can be proud of its contribution in the liberation of Europe. I have witnessed many thousands of German prisoners of war disembark at Portland and in the reverse order hundreds of thousands of American and Allied troops embark for the invasion of Europe from Portland Hard, where there were special bays for reception craft. All this has disappeared into history but instances large and small still linger in my mind.

——

The End